Modern Relationships and Murakami's Sputnik Sweetheart

Spoiler Alert: this post is about the book Sputnik Sweetheart, and contains important plot points from it.

When you think of the word “Longing”, what do you think about?

I imagine hands reaching toward one another, their skin never touching. Or standing on some towering building and looking for the small shape of a place I know.

Do you think of someone particular when you hear that word? Or is it a place that you haven’t been?

In Murakami’s Sputnik Sweetheart, every character is a satellite- a small, metal object, hurling through the emptiness of space. The narrator, who is in love with Sumire, watches as she falls in love with an older woman named Miu, who she refers to as her “Sputnik Sweetheart”. They are all intimate with one another in different ways, but between each of them, an uncrossible distance remains:

“And it came to me then. That we were wonderful traveling companions but in the end no more than lonely lumps of metal in their own separate orbits. From far off they look like beautiful shooting stars, but in reality they’re nothing more than prisons, where each of us is locked up alone, going nowhere. When the orbits of these two satellites of ours happened to cross paths, we could be together. Maybe even open our hearts to each other. But that was only for the briefest moment. In the next instant we’d be in absolute solitude. Until we burned up and became nothing.”

The Sputnik referred to in the story is Sputnik 2, a Russian satellite that was launched into orbit in 1957 with a dog named Laika as its passenger. The word “Sputnik” enters the story from a miscommunication between Miu and Sumire, and is lovingly used to refer to Miu. When thinking of the same little satellite, the narrator pictures the dog gazing out into the “infinite loneliness of space”, looking for something in the blackness.

These images set the tone of the story early on, and we watch as the characters pass out of each other’s lives.

What did you write when you last wrote about someone you know? For me, it was during the last snowstorm, and I was in my room, watching the spotted darkness pass over my window. I wrote about a girl with brown hair that I once walked through the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum with.

The museum has an interesting history: beginning with Gardner’s will for the building to never change after her death, and later involving a theft in the 1990’s. When you visit, now, you’ll find empty spaces in walls with the shadows of paintings, and frames with nothing in them.

I wrote about the time we walked through those halls on a summer night, when she admired the old frames, while I was captivated by the empty spaces. Now, whenever I go, I feel like a ghost, searching for lost time- still captivated by the empty spaces.

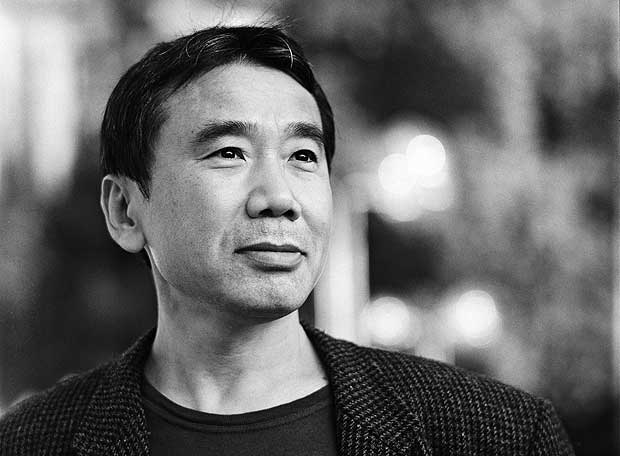

Murakami writes in the same ways. His characters are always recurring in his novels- a man who has affairs with older women, a girl who stares at the moon- and are written as if he knew them. The metaphors he uses feel like memories rather than just imagery:

“Who can really distinguish the sea and what’s reflected in it? Or tell the difference between the falling rain and loneliness?”

His intimacy with these characters feels like the written form of the kind of thoughts that come at night. I can imagine him laying in his bed, awake- his eyes staring at the ceiling- before he turns on a lamp at his bedside to write down a passing thought.

The ease in which modern relationships comprise of missed connections is a paradox that is concerning to me. When Murakami published this book in 2001- five years after the rise of the mobile phone- the rate in which the world was becoming connected by technology had become exponential. Three years later, Facebook was introduced, and grew into a world-wide phenomenon.

In the 1960’s Stanley Milgram ran the “small world experiment”, in which the theory of Six Degrees Of Separation was examined. In the theory, everyone in the world is connected by five intermediate acquaintances- so that if I count all my friends, friend’s friend’s, and so on, I would be connected to all 7 billion people on the planet. In 2011, Facebook analyzed their data, and found that this number is decreasing- from six degrees to five- and is continuing to do so as we become more connected.

However, a common complaint that I hear is that people are becoming lonelier as we become more connected. An article I read theorized that by being connected to so many people, individuals have become interchangable, and therefore connections are less durable than before. We know that we are connected to others, and so, we neglect to maintain our relationships over time.

A part of me wonders if we are fated to be the same kinds of characters that pass through the world of Sputnik Sweetheart. There are many people that have passed in and out of my life, and on occasion, I wonder if our paths will cross again.

I don’t think that I believe in fate. How I cultivate my relationships has always been a choice, either through instinct or through premeditated intention. And after a few years of choosing to find each other again, you know who is here to stay.

When I think of those that leave marks on my life and never return, I know that over time, I’ll find myself thinking like the narrator at the end of the story:

“We’re both looking at the same moon, in the same world. We’re connected to reality by the same line. All I have to do is draw it toward me. I spread my fingers and stare at the palms of both hands, looking for bloodstains. There aren’t any. No scent of blood, no stiffness. The blood must have already, in its own, silent way, seeped inside.”

Laika was the first animal in space, and died from a lack of oxygen on the sixth day of her orbit. In the U.S.S.R., on that same day, Khrushchev said “Now, our first Sputnik is not lonely in its space travels.”